HistoryAlthough it is unknown when Meteora was established, as early as the 11th century AD hermit monks were believed to be living among the caves and cutouts in the rocks. By the late 11th or early 12th century a rudimentary monastic state had formed here. The hermit monks, seeking a retreat from the expanding Turkish occupation, found the inaccessible rock pillars of Meteora to be an ideal refuge. Although more than 20 monasteries were built, beginning in the 14th century, only six remain today. Access to the monasteries was originally extremely difficult, requiring either long ladders lashed together or large nets used to haul up both goods and people. This required quite a leap of faith -- the ropes were replaced, so the story goes, only "when the Lord let them break." The hills themselves are composed of a mixture of sandstone and conglomerate and were formed about 60 million years ago. A series of earth movements caused by the movement of tectonic plates pushed the seabed upwards, creating a high plateau and causing many fault lines to appear in the thick layer of sandstone. Continuous weathering by water, wind and extremes of temperature turned them into huge rock pillars, marked by horizontal lines which geologists maintain were made by the waters of a prehistoric sea. Greek historian Herodotus wrote in the fifth century BC that local people believed the plain of Thessaly had once been a sea. If this was accurate, there was most probably an inundation at the end of the last Ice Age, around 8000 BC |

As we approached the Meteora area, we noticed these strange looking rock formations.

As we approached the Meteora area, we noticed these strange looking rock formations.

A telephoto shot of one of these formations. Thanks to a good road, we would soon be at a monastery at the top of one of them.

A telephoto shot of one of these formations. Thanks to a good road, we would soon be at a monastery at the top of one of them.

The monastery of Saint Stephen, where monastic life began in 1192.

The monastery of Saint Stephen, where monastic life began in 1192.

Other views of the monastery.

Other views of the monastery.

We visted the interesting church and museum there. We were not allowed to take any photographs inside, but we saw some beautiful paintings.

We visted the interesting church and museum there. We were not allowed to take any photographs inside, but we saw some beautiful paintings.

We did have a beautiful view of the city of Kalambaka below.

We did have a beautiful view of the city of Kalambaka below.

From a viewpoint on the way down to Kalambaka we saw three other monasteries.

From a viewpoint on the way down to Kalambaka we saw three other monasteries.

In this telephoto shot of the Grand Meteora we could see the balcony on the far right from which a winch could lower a net for access.

In this telephoto shot of the Grand Meteora we could see the balcony on the far right from which a winch could lower a net for access.

One last monastery.

One last monastery.

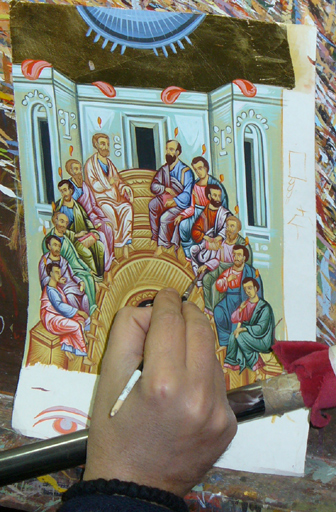

On our way to Athens the next morning we stopped at an iconography workshop. Iconography is the painting of icons (images, pictures or representations) in the Byzantine and Orthodox Christian tradition. Here we are shown the different painting and gilding steps for a typical icon. These icons are painted on canvas and mounted on board. Egg tempera, made from egg yolks and natural minerals, is used for the painting.

On our way to Athens the next morning we stopped at an iconography workshop. Iconography is the painting of icons (images, pictures or representations) in the Byzantine and Orthodox Christian tradition. Here we are shown the different painting and gilding steps for a typical icon. These icons are painted on canvas and mounted on board. Egg tempera, made from egg yolks and natural minerals, is used for the painting.

The minerals used in painting and a painting in progress.

An icon of the nativity with the infant Jesus in a grave, prefiguring His death.

An icon of the nativity with the infant Jesus in a grave, prefiguring His death.

An icon of Christ the Teacher in the prescribed iconic form. In this image of Christ the Teacher, Jesus is presented in a 3/4 length pose, looking directly at the viewer, with his left hand holding the Sacred Word of God and his right hand raised in blessing. He is dressed in the traditional garb of tunic and cloak. His cloak, called in Greek a "himation" is dark blue signifying the mystery of His divine life.

An icon of Christ the Teacher in the prescribed iconic form. In this image of Christ the Teacher, Jesus is presented in a 3/4 length pose, looking directly at the viewer, with his left hand holding the Sacred Word of God and his right hand raised in blessing. He is dressed in the traditional garb of tunic and cloak. His cloak, called in Greek a "himation" is dark blue signifying the mystery of His divine life.

Christ’s halo, the iconographic symbol for sanctity, is inscribed with a cross and the Greek letters omicron, omega, nu, spelling "HO ON." In English, this becomes "Who Am" or "I Am", the name used for God in Exodus 3:14. On the background is written "IC XC", the shortened form of the Greek Iesous Khristos.

The face of Jesus follows ancient traditions. The eyes are large and open, looking directly into the viewer’s soul. The forehead, identified as the seat of wisdom, is high and convex. The nose is long and slender, contributing a look of nobility. The mouth is small and closed in the silence of contemplation. The hair is curled and flowing, recalling the endless flow of time. The neck and body are powerful reminders of His strength and majesty.

Our next stop is Athens.