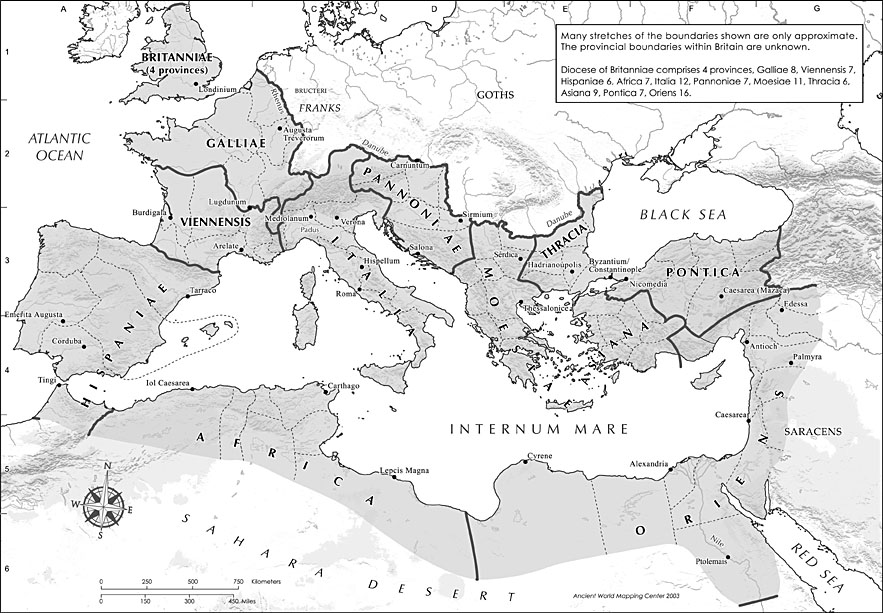

In the western half of the empire, Constantine ruled over Britain, Gaul and Spain, while Maxentius ruled over Italy and North Africa.

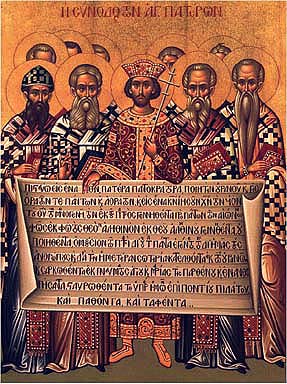

Nicene Creed

Diocletian

began another persecution of Christians in 303 with an edict

requiring that all copies of the Scriptures be publically burned.

Christians lost their civil status and legal rights. Another edict

decreed death for all Christians. Before Diocletian retired as

emporer in 305 he had broken the empire into 4 administrative units

and a power struggle began.

In the western half of the empire,

Constantine ruled over Britain, Gaul and Spain, while Maxentius

ruled over Italy and North Africa.

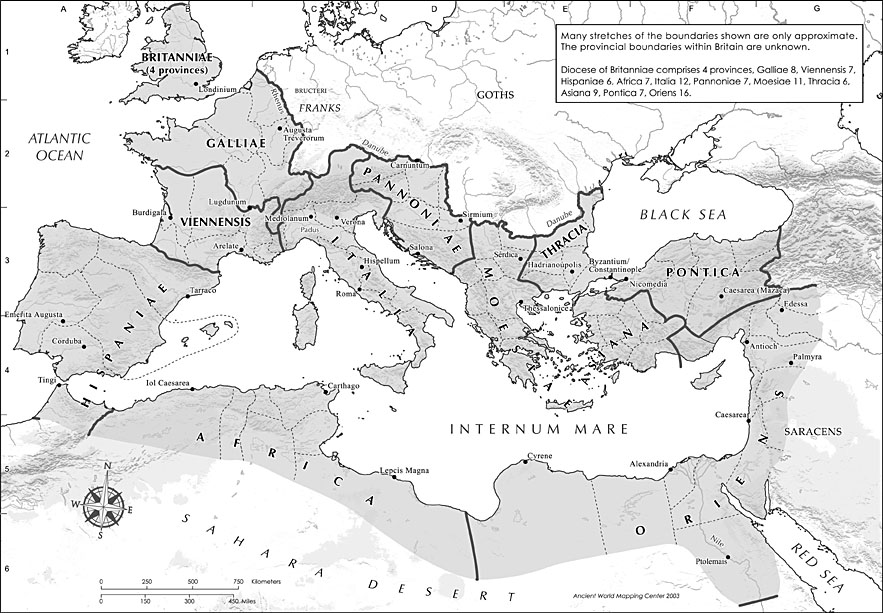

In

312 CE Constantine was about to lead his army in a battle that would

change the world. The soldiers of Maxentius faced him at the Milvian

Bridge outside Rome. The winner would become the Roman Emperor.

Constantine was a pagan who worshipped the sun god, Apollo, and he

was worried about the coming battle. He says he started to pray to

the "Supreme God" for help. Legend has it that a cross

appeared in the sky with and a sign with the words "by this sign

you will conquer". That night in a dream he said he saw Jesus

telling him to use the sign Chi-Rho (the first letters of the name

Christ in Greek) "as a safeguard in all battles". Legend has it that

Constantine ordered the sign to be put on his soldier's shields - and

won the battle.

Painting by Raphael.

Painting by Raphael.

It is more likely that he added the cross to the typical eagle standard of the Roman army.

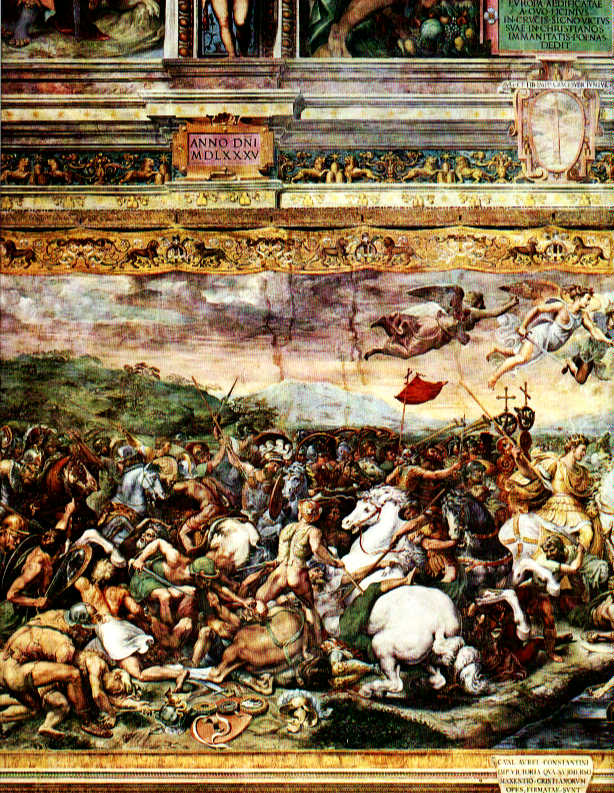

Constantine believed that he had won because of the God of the Christians and he became a Christian, which helped Christianity in many ways. Followers were safe from persecution. Constantine's adherence to Christianity ensured exposure of all his subjects to the religion. He also made Sunday an official Roman holiday so that more people could attend church, and made churches tax-exempt. However, many of the same things that helped Christianity spread subtracted from its personal significance and promoted corruption and hypocrisy. Many people were attracted to the Church because of the money and favored positions available to them from Constantine rather than from piety. The growth of the Church and its new-found public aspect prompted the building of specialized places of worship where leaders were architecturally separated from the common attendees, which stood in sharp contrast to the earlier house churches which were small and informal. Many of the early churches took on the form of the Roman basilica, a building used by the Romans for public gatherings: law courts, financial centers, army drill halls, and reception rooms. These basilicas regularly had an architectural form we call an apse. The apse was a semi-circular projection usually off the short wall of the rectangular building. The apse was the site of the law court.

The Palace Basilica of Constantine in Trier from 305.

This a drawing of the Old St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. This basilica was begun in 323 and was destroyed in 847.

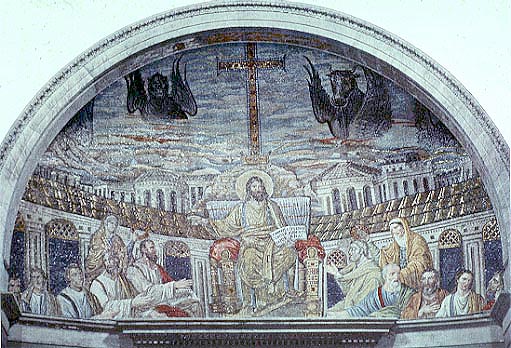

An apse mosaic from 390.

Basilica of St. Paul-Outside-the-Walls, originally built in 380, reconstructed in the 19th century in the same general size and style.

The Basilica di S. Apollinare of the 6th century.

The mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna(420), initially intended as a chapel.

Constantine believed that the Church and the State should be as close as possible. He made December 25th, the birthday of the pagan Unconquered Sun god, the official holiday it is now--the birthday of Jesus. It is likely that he also instituted celebrating Easter and Lent based on pagan holidays. From 330-337 Constantine stepped up his destruction of paganism, and during this time his mother, Helen, made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and began excavations to recover artifacts in the city. This popularized the tradition of pilgrimages in Christianity.

The Doctrine of the Trinity in the early church

the early Christian church inherited worldviews and themes from both Jewish culture and Hellenism. One of the most profound structures the church inherited was the idea of a three-level universe.In other words, from the Jewish culture and (to a certain extent) from Roman Hellenism, Christianity was given the notion that the world divides into three stacked "realms": Heaven, the Spirit World and the Created world. The question the Patristic writers faced, then, is which part of the three-level universe is the right place for Jesus? This question forms the heart of what we might call the early church's Christological problem.

The doctrine of God has always been of primary importance to Christianity. A correct view of God is pivotal to every other doctrine that the church holds dear. The most significant developments in articulating the doctrine of the Triune God took place in the 4th century, A.D. with a group of men known as the Theologians. Though the earliest church fathers had affirmed the doctrine of the apostles, they were focused on their pastoral duties to a persecuted church and thus were unable to compose doctrinal treatises. With the relaxing of the persecution of the church during the rise of Constantine to power in the Roman empire, the stage was set for wide-ranging ecumenical dialogue. The resultant councils and creeds did not discover or create Trinitarian doctrine. The Theologians, responding to serious heresies such as Arianism, articulated in the creeds the truths that the orthodox church had believed since the time of the apostles.

The Arian Controversy

With the end of state persecution against the church, the entire Roman Empire was available for openly Christian teaching. Unfortunately, it became much easier for heretics to develop a wide following, particularly if they claimed that their teaching came from a correct interpretation of the Bible. Perhaps the most prominent heretic of the early church, Arius (d. 336 A.D) , who was a presbyter in Alexandria. Arius, having been schooled in Antioch, would inevitably clash with the rival tradition in Alexandria. Arius did not strictly teach the doctrine of his predecessors but his heavy emphasis on absolute monotheism led him astray. This emphasis led to the complete subordination of Christ to the Father, to the point that Jesus was a created being. Referring to this creation, Arius states,

We praise Him (God) as without beginning because of Him (Jesus) who has a beginning. And adore Him as everlasting, because of Him who in time has come to be. The Unbegun made the Son a beginning of things originated; and advanced His as a Son to Himself by adoption. He has nothing proper to God in proper subsistence. For He is not equal, no, nor one in essence with Him.

In addition, out of his unbridled zeal for monotheism, Arius misinterpreted the Greek Logos in John 1:1 as “wisdom,” and correlated it with the Septuagint’s version of Prov. 8:22, which states that wisdom was God’s first creation. This incorrect translation and correlation led Arius to teach that the Son of God was the first creature that God created. Arius, in his work Thalia, explicitly denies the eternality of the Son:

God was not always Father; but there was when God was alone and was not yet Father; afterward He became a Father. The Son was not always; for since all things have come into existence from nothing, and all things are creatures and have been made, so also the Logos of God Himself came into existence from nothing and there was a time when He was not; and that before He came into existence He was not; but He also had a beginning of His being created.

Alexander (d. 328 A.D.), the bishop of Alexandria, was the first to take offense at the teachings of the presbyter Arius. Alexander sought to have Arius excommunicated in 320/21, but Arius found refuge with Eusebius of Nicomedia, a bishop, himself a follower of Lucan.

However, the most forceful opponent that Arius contended with was Athanasius (ca. 296-373 A.D.), who trained under Alexander in Alexandria. Upon Alexander’s death in 328, Athansius succeeded his mentor as the bishop of Alexandria. The core of Athanasius’ soteriology, which caused his great disagreement with Arius, was that only God could save humanity. Because God chose to send a Savior through whom this salvation would be accomplished, this Savior Himself must also be fully divine. With this background Athanasius condemned Arianism, for if the Savior must in fact be divine, and Jesus was created unlike the Father, then Christians were practicing polytheism. Thus on two main points Athanasius was repulsed by Arian doctrine: (1) it led to polytheism, and (2) it taught that salvation originated in creation, not with the Creator.

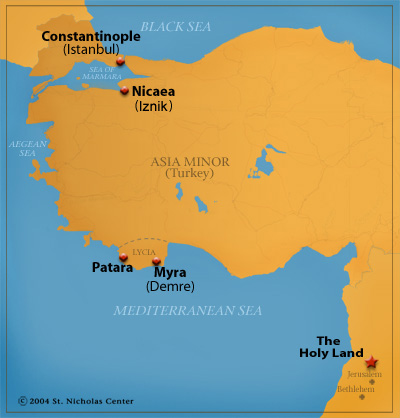

The Council of Nicea

In

324 Constantine gained sole control over the entire Roman Empire(East

and West), an empire that was greatly divided over the debate between

Arius and Alexander. In order to bring unity to the empire,

Constantine ordered a council to resolve the matter at Nicea in 325.

Comparing the Apostle's Creed and the Nicene Creed

The Nicene Creed is different from the Apostle's Creed. The Nicene Creed is a creed that tries to define, to use more precise language for the church's faith, to set boundaries. It even introduces a word that is not in the Bible, homoousios, of one substance or being, because the bishops felt that it helped explain how God could be one yet twofold (the debate about the Holy Spirit will follow two generations later). With that term the council fathers wished to say that in whatever way God is God, Christ also is God. The term "begotten" (which is biblical) means that he comes into being eternally from the Father—he is not made like human beings.

Both creeds find their chief purpose in explaining Jesus as a being with both humanity and some form of divine nature. The Apostle's creed, however, stops short of explicitly naming Jesus as God, and does not elaborate in the slightest about the nature of relationship of the Holy Spirit to the Father or Jesus. The Nicene creed, in contrast, makes explicit the divinity of both the Spirit and Jesus (as the Son).

The Nicene Creed and the Canon of Scripture

The New Testament and the Nicene Creed are deeply entangled with each other. The wording and the concepts in the Nicene Creed come from the New Testament—in fact, one of the most important debates at the Council of Nicea concerned whether it is proper to include a word in the Nicene Creed that does not occur in the New Testament. On the other hand, at the time that the Church issued the official canon of the New Testament, it customarily compared writings to the Nicene Creed to determine if they were orthodox. So you are correct if you say that the Nicene Creed proceeds from the New Testament, and you are correct if you say that the New Testament is certified by the Nicene Creed.

To put it more precisely, the Nicene Creed and the canon of the New Testament were formed together as part of the same process.

The

Aftermath of the Council.

Unfortunately, the Council of

Nicea did not completely resolve the debate over Arianism. The

problem surrounded the use of the Greek homoousia, which the

council used to describe the relationship between the Son and the

Father. The Western theologians understood the term as

Tertullian had used it, to mean unity of substance or essence.

The Eastern theologians understood it only to affirm the divinity of

the Son, and thus feared that it left the door open for Modalism.

This misunderstanding of terminology prevented the church from being

able to completely do away with the Arian heresy, and left the door

open for the Arians to remain a prominent group of theologians.

The

Arians set out discrediting their opponents after the council,

finally winning the approval of Constantine on his deathbed in 336.

Constantine’s son, Constantius, became a defender of Arianism

in the eastern portion of the Roman Empire. The opponents of

Nicea, primarily Arians, splintered into three distinct groups.

The question about the Holy Spirit and its part in the Trinity was not settled until the council at Constantinople in 381.

The Arian position has been revived in our own day by the Watchtower Society (the Jehovah's Witnesses), (http://www.spurgeon.org/~phil/articles/deity.htm) who explicitly hail Arius as a great witness to the truth. Gnosticism is also present in the book, The Da Vinci Code, and the movie Matrix.