We begin with a look at the Reformation in the German-speaking area of Switzerland.

ULRICH ZWINGLI (1484-1531)

On January 1, 1484, seven weeks after Martin Luther was born, there was born in Wildhaus in the German-speaking part of Switzerland a boy who was to be known to history as Ulrich Zwingli. His experience differed greatly from that of Luther. He never lived as a monk in a convent. He did not have Luther's deep consciousness of sin, and he knew nothing of Luther's fearful spiritual struggle to gain salvation. Luther emerged out of the darkness of medievalism, and had been educated in scholastic theology; he studied the great writings of the Church Fathers and other works written under the influence of the medieval Church. Zwingli received his education under the influence of the Renaissance humanists, that is, under the influence of the new interest in the ancient writings of the Greeks and Romans, which had recently been brought to the western world.

Zwingli studied in Basel, Bern, and Vienna. In 1506 he received the degree of Master of Arts. Thereupon he entered the service of the Church. In 1519 he became pastor of the church of Zurich, the most important city in that part of Switzerland. He was also chaplain in the army of the city of Zurich. Shortly after arriving in Zurich, the Black Plague decimated the city, claiming about a quarter of its population. Zwingli ministerd to the vicitims and became ill himself, but recovered.

At first Zwingli stood strongly under the influence of Erasmus, with whom he became personally acquainted. He made a thorough study of the New Testament and of the Church Fathers. Originally he had no intention of attacking the Roman Church. Like Erasmus, he hoped to bring about improvements gradually through education. He first arrived at certain reformatory ideas independent of Luther. Later he came under Luther's influence, and moved further and further away from the position of Erasmus.

In 1518 Zwingli attacked indulgences. The stand Luther took in the Leipzig debate and his burning of the papal bull inspired Zwingli to make a systematic attack on the Roman Church.In 1519 Zwingli began to systematically preach through the New Testament - beginning with the Gospel of Matthew. He opposed indulgences and preached the Gospel. He also secretly married!

One of his direct actions against the Church was his participation in a meeting which objected to the Lenten rule of fasting and two smoked sausages were cut up and distribued to those present. This action and sermons about Christian freedom were possibly influenced by a tract by Luther. In 1523 the City Council of Zurich voted to become Protestant by supporting Zwingli’s reforms.

Images were removed from the church buildings in Zurich. The mass was abolished. Altars, relics, and processions were discarded. The government of the church and the care of the poor were placed in the hands of the city council. The school system was reformed. From Zurich the Reformation of the Church spread to several of the Swiss cantons; but many cantons remained Catholic.

Zwingli differed from Luther in his idea of the Lord's Supper. As we have seen, Luther taught that the body of Christ, having become everywhere present at His ascension, is actually present in the bread and the wine(consubstantiation.) Zwingli taught that the body of Christ is now only in heaven, and that the words,"This is my body" mean "This signifies my body." According to Zwingli the bread and the wine are only symbols of the body and blood of Christ and the Supper is only a memorial ceremony.

In October, 1529, Luther and Zwingli held a Colloquy (conference) in Marburg, but the two leaders could not come to an agreement on the Lord's Supper. For a time, Zwingli had considerable influence in Switzerland and southern Germany: in Basle (Johannes Oekolampadius), Berne (Berchtold Haller and Niklaus Manuel), St. Gall (Joachim Vadian), to cities in Southern Germany and via Alsace (Martin Bucer) to France.

Of the total 13 political territories in the Swiss Confederation, seven were Roman-Catholic, four were Reformed and in two of them both confessions existed. Armed conflicts arose between the Protestant and Catholic parties, culminating in the infamous defeat of the Protestants at Kappel (near Zurich) in 1531, where Zwingli also died. Zwingli's last words were: "They can kill the body - but not the soul!"

Bullinger, Heinrich (1504-1575)

After

the death of Ulrich Zwingli in 1531, Bullinger became pastor of the

principal church in Zürich and a leader of the reformed party in

Switzerland. He played an important part in compiling the first

Helvetic Confession (1536), a creed based largely on Zwingli's

theological views as distinct from Lutheran doctrine. In 1549 the

Consensus Tigurinus, drawn up by Bullinger and Calvin, marked the

departure of Swiss theology from Zwinglian to Calvinist theory. His

later views were embodied in the second Helvetic Confession (1566),

which was accepted in Switzerland, France, Scotland, and Hungary and

became one of the most generally accepted confessions of the reformed

churches. He wrote a life of Zwingli and edited his complete works.

There is mmuch more information on Bullinger at http://pages.slc.edu/~eraymond/reformation/three.html

We now consider the Reformation in the French speaking part of Switzerland.

We first look at the beginnings of the Reformation in France, since these events were important in the French speaking part of Switzerland. The early years of the sixteenth century in France were graced by some great Christian humanist intellects: Erasmus, Lefèvre d'Etaples, and others. Marguerite de Navarre, François I's sister, was a great patron, and François I as an enlightened Renaissance prince himself, was sympathetic and once offered Erasmus the leadership of his new College de France, founded to promote classical learning. The Bishop of Meaux, Guillaume Briçonnet, gathered a circle of inquiring intellects and passionate, reform-minded preachers around him there during the early 1520s. There was no particular intention of breaking from the church at this time, merely a passion for improving it.

Lefèvre d'Étaples, Jacques (1450-1536)

A priest, Lefèvre studied in Italy, where he was influenced by Neoplatonism. In 1507, he was made librarian at the abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. He became famous for his commentary on the epistles of St. Paul (1512) and his edition of the works of the mystic, Nicholas of Cusa (1514). Caught up in the spirit of criticism of the abuses of the Roman Catholic Church, he became a leading figure of Christian humanism. Although advocating some of the ideas later integral to the Reformation, he believed, like Erasmus, in reform from within and refused to break with the church. Nevertheless, he was subjected to suspicion and persecution. In 1521, the Sorbonne condemned as heretical his book on the three Marys, but Francis I and his sister Margaret of Navarre prevented further action against him. The preceding year, Lefèvre had left Paris for Meaux, where his friend, Briçonnet, now bishop of this city, was to appoint him his vicar-general in 1523. He continued his biblical studies, publishing a French translation of the New Testament (Paris, 1523) and of the Psalms (Paris, 1525); an explanation of the Sunday Epistles and Gospels (Meaux, 1525). Forced to seek refuge in Strasbourg in 1525, he returned the following year as tutor to the royal children and librarian in the château at Blois. His last years were spent at Nérac, under the protection of Margaret of Navarre. The Protestant reformer Guillaume Farel was one of his pupils. Lefèvre d'Étaples translated the Bible into French (1523-30)

WILLIAM FAREL (1489 - 1565)

In 1520, Farel joined Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples at Meaux to aid in church reform and to establish an evangelical school for students and preachers. Soon his iconoclastic ideas made him suspect, and he left for Switzerland, where he did most of his work. His fearless and eloquent evangelism aroused both support and opposition. He received permission to spread the reformed doctrine throughout the canton of Bern.

In 1532(?), Farel began to preach in the Geneva, persuading the Council of Twenty-Five to his views. Aided by Peter Viret and Antoine Froment, Farel aroused such support that nearly all the Catholic clergy fled, the Mass was abolished, relics removed from the churches, ecclesiastical properties taken for Protestant purposes. Citizens were exhorted to delare allegiance to The Gospel, and those refusing to attend Reformed Services were banished.

The opposition of the bishop forced him to leave Geneva in 1532, but he returned in 1533 to lead a public disputation in favor of the Reformation. The people declared in favor of Farel and his colleagues, and in 1535 the town council formally proclaimed the adoption of the Reformation. It was to this reformed Geneva that Calvin came, when Farel was 47 and Calvin was 20 years younger. Recognizing Calvin's ability, but reacting to Calvin's reluctance, Farel threatened Calvin with a holy curse if he preferred private studies to the dangerous teaching of "The Word".>

Farel entreated Calvin to assist in the organization of the new Protestant republic. The two men drew up a statement of doctrine and immediately instituted widespread reform of church practices. These measures were too sudden and too strict to be generally accepted, and Calvin and Farel were forced to leave Geneva in 1538. Farel went to Basel and then to Neuchâtel, where he worked unceasingly for the return of Calvin to Geneva, which he achieved in 1541. Throughout his life he remained a confidant and consultant of Calvin.

JOHN CALVIN (1509-1564)

Calvin was born in northwestern France, twenty-five years after the birth of Martin Luther. His actual name, Jean Cauvin, became "Calvin" years later when as a scholar he adopted the Latin form (Calvinus). From a middle-class status Calvin’s father, Gerard, after serving the church in various offices including notary public, had risen to become the bishop’s secretary. To enable his son to advance to a position of ecclesiastical importance, Calvin’s father saw to it that he received the best possible education. At age fourteen Calvin was enrolled in the University of Paris. There he eventually attended the College de Montaigu, the same institution Erasmus had attended (and hated) some thirty years earlier. Although Calvin pursued a similar career in theology, for several reasons his life took an unexpected turn. First, the new learning of the Renaissance (humanism) was waging a successful battle against scholasticism, the old Catholic theology of the late Middle Ages. Calvin encountered the new learning among the students and was powerfully attracted to it. Second, a strong movement for reform in the church, led by Jacques Lefevre d’Etaples, had been flourishing in Paris not far from the university. Calvin became a close friend of some of Lefevre’s disciples. Third, Luther’s writings and ideas had circulated in Paris for some time, causing a moderate stir; Calvin undoubtedly became familiar with them during his student years. Finally, Calvin’s father had a falling-out with the church officials in Noyon, including the bishop. Thus in 1528, just as Calvin had completed his master of arts degree, his father sent word for him to leave theology and study law. Dutifully, the son migrated to Orleans, where France’s best law faculty was located.

Calvin

threw himself into his law studies, winning acclaim for his mastery

of the material. He often taught classes for absent professors. After

about three years of study at Orleans, Bourges, and Paris, he had

earned a doctorate in law and his law license. Along the way he had

learned Greek and had immersed himself in the classical studies,

which were of great interest to the contemporary humanists. He

associated closely with a group of students at odds with the

teachings and practices of Roman Catholicism. When his father’s

death in 1531 left Calvin free to choose the career he favored, he

did not hesitate. Excited and challenged by the new learning, he

moved to Paris to pursue a scholarly life.

Little

is known about Calvin’s conversion except that it occurred

between 1532 and early 1534, when his first religious work was

published. He said: "God

subdued and brought my heart to docility." When he contibuted to

a talk by the rector of the University of Paris in 1533, which

strongly advocated reform along Lutheran lines, the rector was

accused of heresy, they both fled the city.

When the French

king, Francis I (reigned 1515–1547), decided that persecution

was the solution to the Protestant problem, Calvin realized it was no

longer safe to live in Paris or anywhere else in France. For the rest

of his life, therefore, he was a refugee.

In Basel (Switzerland) early in 1536 Calvin published the first edition of his Institutes of the Christian Religion. The work, which underwent several revisions before its final exhaustive edition in 1559, was without question one of the most influential handbooks on theology ever written. Its publication marked Calvin as a leading mind of Protestantism and kept him from pursuing the quiet scholarly life he had hoped for. As he described it, "God thrust me into the fray."

Traveling to Strassburg (a free city between northern France and Germany) in 1536, Calvin stopped for the night in Geneva. With the help of its Swiss neighbors, Geneva had recently declared its political independence from the Holy Roman Empire. Only two months earlier under the prodding of fiery reformer William Farel, it had declared allegiance to Protestantism. Farel, who had been working in Geneva for nearly three years, convinced Calvin to stay there. The rest of his life was given mostly to the work of reform in Geneva.

Calvin immediately set to work reorganizing the church and its worship. Under Catholicism the Genevan church had observed Communion only two or three times a year; Calvin, who favored a weekly celebration, recommended a monthly observance as an interim compromise. Calvin’s emphasis on church discipline grew directly out of his high regard for the Lord’s Supper. To oversee that the sacrament was taken worthily Calvin instituted a church board (the Genevan Consistory) which insured that all communicants (those participating in Communion) truly belonged to the "body of Christ" and also were practicing what they professed. Calvin also introduced congregational singing into the church—"to incite the people to prayer and to praise God."

When

the city council disagreed with the proposals of Calvin and Farel,

they were banished from the city in April, 1538.

Calvin spent

the following three years (1538–1541) in Strassburg, enjoying

his long-sought period of peaceful study. There he associated closely

with Martin Bucer, whose ideas, particularly on predestination, the

Lord’s Supper, and church organization, markedly influenced

Calvin’s own. In Strassburg Calvin also pastored a congregation

of Protestant refugees from France, organizing its church government

after what he believed to be the New Testament pattern and compiling

a liturgy and a popular psalm book, which eventually became the

Genevan Psalter (1562.)

The liturgy John Calvin used in the French refugee church in Strasbourg in 1539 and the basis of his liturgy when he became a pastor in Geneva.

Public

Confession of Sins

Public Absolution of Sins

Psalm/Hymn

Prayer

for Illumination

Psalm/Hymn

Scripture

Lesson

Sermon

Singing

of the Apostles’ Creed

Pastoral

Prayer followed by the Lord's Prayer

Instruction

on the Holy Supper

The

Words of Institution

Distribution

of the Elements

Psalm/Hymn

Prayer

of Thanksgiving

Benediction

Committal

Depart! The Spirit of the Lord go with you unto eternal life! Amen.

In

1541 the city of Geneva implored him to return. The prospect

horrified Calvin, who regarded Geneva as "that cross on which I

had to perish daily a thousand times over." Nevertheless, at

Farel’s insistence, he reluctantly returned.

The city

council, now much more attentive to Calvin’s proposals,

approved his reforms with few changes. He began a long, unbroken

tenure as Geneva’s principal pastor. Though constantly

embroiled in controversy and bitterly opposed by strong political

factions, Calvin pursued his tasks of pastoring and reform with

determination.

In addition to traditional areas of Christian

works, such as arranging for the care of the elderly and poor, many

of Calvin’s reforms reached into new areas: foreign affairs,

law, economics, trade, and public policy. Calvin exemplified his own

emphasis that in a Christian commonwealth every aspect of culture

must be brought under Christ’s lordship and treated as an area

of Christian stewardship. Calvin worked on the recodification of

Geneva’s constitution and law, mollifying the severity of many

of the city’s statutes and making them more humane. In

addition, he helped negotiate treaties, was largely responsible for

establishing the city’s prosperous trade in cloth and velvet,

and even proposed sanitary regulations and a sewage system that made

Geneva one of the cleanest cities in Europe. Although the legal code,

much of it adopted upon Calvin’s recommendations, seems strict

by modern standards, nonetheless it was impartially applied to small

and great alike and was approved by the majority of Geneva’s

citizens. As a result, Geneva became a "Christian republic,"

which the Scottish reformer John Knox called "the most perfect

school of Christ . . . since the days of the apostles." Church

and state served as "separate but equal" partners.

Besides the Institutes, Calvin also wrote commentaries on most of the books of the Bible as well as the Geneva Catechism, first in 1536 with revisions in 1542 and 1560. He was a driving force behind the Genevan Psalter, although most of the work was done by Farel and Beza and musicians such as Bourgeois. He also encouraged his brother-in-law William Whittingham to write the Genevan Bible, published in 1599 and very popular in England and among the Puritans.

During Calvin's last years, Geneva was home to many religious refugees who carried away the desire to implement a Genevan reform in their own countries. His personal letters and published works reached from the British Isles to the Baltic. The Geneva Academy, founded in 1559, extended the circle of his influence. His lucid use of French promoted that language much as Luther's work spread the influence of German. By the time he died, Calvin, in spite of a reserved personality, had generated profound love among his friends and intense scorn from his enemies. His influence, which spread throughout the Western world, was felt especially in Scotland through the work of John Knox.

Calvin’s motto was "Promptly and sincerely in the work of God."

Beza, Theodore (1519-1605)

In 1548 he joined John Calvin at Geneva and soon became his intimate friend and chief aid. From 1549 to 1558, Beza was professor of Greek at Lausanne, where he wrote De haereticis a civili magistratu puniendis (1554), a defense of the conduct of Calvin and the Genevan magistrates in the notorious trial and burning of Servetus. In 1558 he became professor of Greek at Geneva, and in 1564 he succeeded Calvin in the chair of theology at Geneva. Beza came to be regarded as the chief advocate of all reformed congregations in France, serving with distinction at the Colloquy of Poissy. He was of great importance in aiding the edition of the Greek and Latin versions of the New Testament, and he gave Codex D, or Codex Bezae, one of the most important manuscripts of the Bible, to Cambridge Univ.

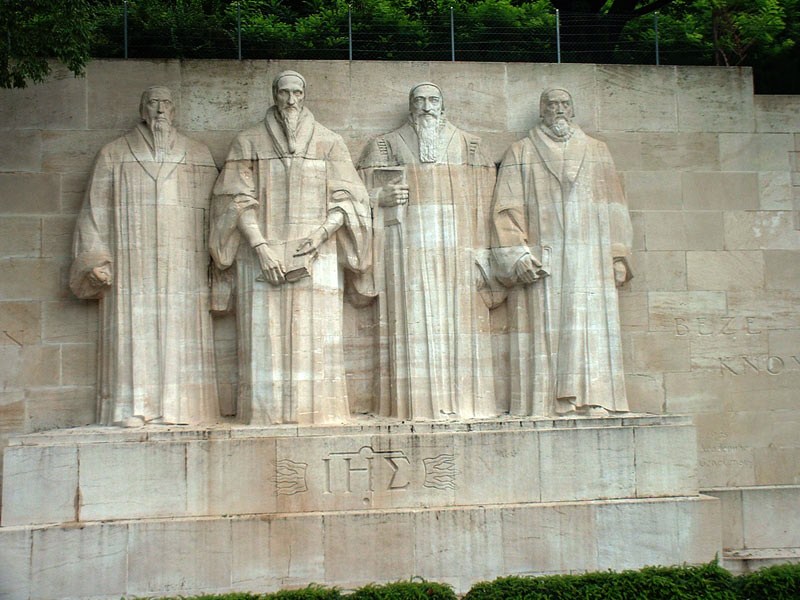

The International Monument at Geneva

The International Monument of the Reformation at Geneva is impressive with the large statues of four of the major Reformers: Farel, Calvin, Beza and Knox. But there is much more to this monument in taht it shows how the Reformation influenced many countries.

At the left, there is a monument to the Edicts of the Reformation, ratified by the people of Geneva on May 21, 1536. The first bas-relief shows Frederick, the founder of the Prussian state, welcoming the Huguenots exiled when the Edict of Nantes was repealed. The statue is of Frederick William (1620-1688.) The second bas-relief commenorates the Declaration of Independence of the United Provinces(Northern Netherlands on July 6, 1581. A statue of William the Silent (1533-1584) is to the right of the bas-relief.

The left bas-relief is of Henry IV of France signing the Edict of Nantes in 1598 giving the Huguenots freedom in France. The statue is of Gaspard de Coligny. The bas-relief on the right is about the Swiss Reformation, showing the first chid presented for Reformed baptism. Viret is in the pulpit and Farel is seated behind him. The two large statues are of Farel and Calvin.

The two large statues are of Beza and Knox. The bas-relief shows John Knox preaching in St, Giles Church in Edinburgh. The statue is of Roger Williams and the bas-relief shows Williams aboard the Mayflower. The words above it are part of the Mayflower Compact. The missing statue at the right of this picture is of Olver Cromwell.

The bas-relief is of the crowning of William and Mary and the words are those of the Declaration of RIghts of the English People. The statue is of Etienne Bocskay, a Hungarian reformer. THe bas-relief show Bocskay bringing the Treaty of Venice to the Diet of Kassa.