History

Mycenaean is the term applied to the art and culture of Greece from ca. 1600 to 1100 B.C. The name derives from the site of Mycenae in the Peloponnese, where once stood a great Mycenaean fortified palace. Mycenae is celebrated by Homer as the seat of King Agamemnon, who led the Greeks in the Trojan War. In modern archaeology, the site first gained renown through Heinrich Schliemann's excavations in the mid-1870s, which brought to light objects whose opulence and antiquity seemed to correspond to Homer's description of Agamemnon's palace. The extraordinary material wealth deposited in the Shaft Graves at Mycenae (ca. 1550 B.C.) attests to a powerful elite society that flourished in the subsequent four centuries.

During the Mycenaean period, the Greek mainland enjoyed an era of prosperity centered in such strongholds as Mycenae, Tiryns, Thebes, and Athens. Local workshops produced utilitarian objects of pottery and bronze, as well as luxury items, such as carved gems, jewelry, vases in precious metals, and glass ornaments. Contact with Minoan Crete played a decisive role in the shaping and development of Mycenaean culture, especially in the arts. Wide-ranging commerce circulated Mycenaean goods throughout the Mediterranean world from Spain and the Levant. The evidence consists primarily of vases, but their contents (oil, wine, and other commodities) were probably the chief objects of trade.

Besides being bold traders, the Mycenaeans were fierce warriors and great engineers who designed and built remarkable bridges, fortification walls, and beehive-shaped tombs—all employing Cyclopean masonry—and elaborate drainage and irrigation systems. Their palatial centers, "Mycenae rich in gold" and "sandy Pylos," are immortalized in Homer's Iliad and Odyssey. Palace scribes employed a new script, Linear B, to record an early Greek language. In the Mycenaean palace at Pylos—the best preserved of its kind—Linear B tablets suggest that the king stood at the head of a highly organized feudal system. By the late thirteenth century B.C., however, mainland Greece witnessed a wave of destruction and the decline of the Mycenaean sites, and the withdrawal to more remote refuge settlements.

After seeing the mostly Roman ruins of Ancient Corinth we were able to see the remains of a much older civilization, that of the Mycenaeans, from about 1600 to 1100 B.C.

After seeing the mostly Roman ruins of Ancient Corinth we were able to see the remains of a much older civilization, that of the Mycenaeans, from about 1600 to 1100 B.C.

Here we see a Mycenaean tomb, known as the Treasury of Artreus or more commonly the Beehive Tomb. This is the most impressive of the "tholos" tombs, constructed around 1250 B.C. Tombs such as these were built into hillsides to hide their location from would-be thieves. This facade is about 34 feet high.

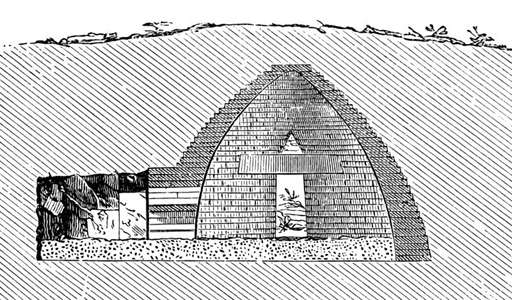

This is a drawing to show how the tomb was built into a hillside. The door opens on to a rotunda, 48 feet in diameter and 44 feet high, with a masonry domed vault of 33 regular courses; some blocks bore a metal decoration.

This is a drawing to show how the tomb was built into a hillside. The door opens on to a rotunda, 48 feet in diameter and 44 feet high, with a masonry domed vault of 33 regular courses; some blocks bore a metal decoration.

This door has a pyramidal shape which is also found in Egypt, and which reappears in classical architecture. The lintel is made up of two enormous blocks; the inner one weighs about 120 tons. The void triangle above it is characteristic of Mycenaean architecture: it serves to deflect the thrusts of the upper part of the building on to the supports of the door.

A view of the interior wall and the doorway from the inside.

From the parking lot we could see the fortifications of a Mycenean palace in the distance.

From the parking lot we could see the fortifications of a Mycenean palace in the distance.

In the museum there we saw a model of the palace and fortifications.

In the museum there we saw a model of the palace and fortifications.

There were also beautiful displays of Mycenaean pottery, from 1000-1100 BC on the left, 1200-1300 BC in the center and from 1600-1700 BC on the right.

We were then ready to begin the hike up to the palace.

We were then ready to begin the hike up to the palace.

We soon reached the Lion Gate.The twin lions shown here flanking a pillar were positioned above the main entrance to the citadel of Mycenae. The gate was about 10 feet wide and 10 feet high; the carved stone with the lions is over nine feet high. It forms what is called a "relieving triangle", because the carved slab weighs much less than the stones to the right and left; this reduced pressure on the lintel block below it. That block weighs two tons or so. The door was made up of two wooden leaves opening inward.

We soon reached the Lion Gate.The twin lions shown here flanking a pillar were positioned above the main entrance to the citadel of Mycenae. The gate was about 10 feet wide and 10 feet high; the carved stone with the lions is over nine feet high. It forms what is called a "relieving triangle", because the carved slab weighs much less than the stones to the right and left; this reduced pressure on the lintel block below it. That block weighs two tons or so. The door was made up of two wooden leaves opening inward.

The lions originally had heads made of metal, but they have long since disappeared. The column the two lions stand beside perhaps represented the god of the royal house; the lions served to guard the entrance.

The lions originally had heads made of metal, but they have long since disappeared. The column the two lions stand beside perhaps represented the god of the royal house; the lions served to guard the entrance.

A circle grave found outside the inner walls.

A circle grave found outside the inner walls.

It was a fairly hard walk to the top of the hill and there were not much to see in the way of ruins, but the views of the countryside were spectacular.

The bus was waiting for us at the parking lot and we started walking down the hill.

The bus was waiting for us at the parking lot and we started walking down the hill.

Another circle grave as we walked down the hill

Another circle grave as we walked down the hill

The Lion Gate from inside the palace.

The Lion Gate from inside the palace.

One last look at the palace.

One last look at the palace.

Tomorrow we begin a cruise and we go to Mykonos.